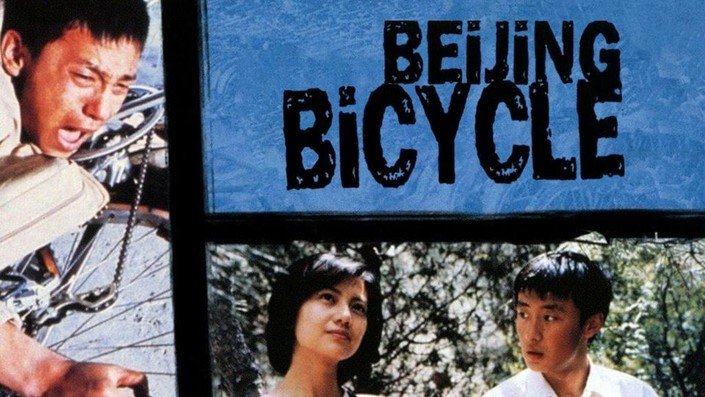

In 1948, director Vittorio De Sica made The Bicycle Thief, the quintessential blueprint of neorealism, a drama widely considered one of the greatest films ever produced. It was shot in the streets of Italy with non-professional actors, and tells about the haves, the have-nots, and the desperate. For the uninitiated, the classic tale is motivated by the theft of a poor man’s bicycle, an item which he must have in order to work. Fifty-three years later, Chinese writer-director Wang Xiaoshuai (So Close to Paradise) presents another story about class differences, shot in the streets of Beijing with non-professional actors, about a young man who needs to retrieve his stolen bike to keep his courier job. Homage? Theft? Gentle borrowing? What difference does it make when the result is delivered with too heavy a hand, and is just too slow to be involving?

Beijing Bicycle is introduced with a captivating style young men, mostly from poor farm families, appear on-camera individually and address the audience as they are interviewed for prestigious bike messenger positions. We hear an interviewer off-screen, but only witness these nervous, determined, sometimes blank faces, telling their stories in return for a chance at urban success. The narrative then follows one staffer, Guei (Cui Lin), as he zips through Beijing making deliveries to upscale office buildings, saving his earnings so that he can own his company bicycle.

Upon entering these city towers, Guei tends to snap his eyes wide open and spin around dreamily with his head in the air. For a humble kid who seems intent on making his way and affecting a professional tone, his response seems a little overdone, and it’s a simple example of Wang’s tendency to overstate the obvious. Clearly, Guei’s a pull yourself by the bootstraps type it doesn’t seem necessary to turn him into a 5 year old just to drum up a little more sympathy for his position.

Early in the film, Guei experiences his first real conflict when a confusing delivery to a health salon (he’s looking for a Mr. Zhang he’s told to try searching for Zhang Yimou ha!) lands him in hot water for taking a shower without paying for it. His feeble attempt at escaping the situation is blatantly lifted from the closing act of De Sica’s classic, but in deference to the Italian master, the idea and similar execution still work, all these years later. And it also lets us know that Wang will be giving us more of the same, in story and style.

With the issue at the spa, Guei’s problems have just begun. One day away from owning his treasured bike, it is stolen, and no amount of begging and pleading can help him keep his job. But unlike De Sica’s Antonio, our young hero actually finds his bicycle (um in Beijing? Well, if you say so…). It was resold to another young man, Jian (Li Bin), whose parents have been promising him a bike, but have never come through. Jian, like Guei, also sees the bicycle as a social necessity, and neither kid is willing to give it up. Their worlds have clashed, and they are at a stalemate.

And from there, Wang’s film feels like a bit of a stalemate too. Bike is spied. Bike is stolen. Bike is found. Fight ensues. Bike is stolen back. The whole process seems a bit tedious, but to be fair, perhaps there is some value in seeing how fruitless the whole situation is. Nonetheless, we see the same scenarios repeated, similar arguments rehashed, and the scope of the film becoming smaller and smaller.

To Wang’s credit, his directorial style is a big plus in the film, and shows that he has a deft eye for changing points of view, and an exciting, quiet, voyeuristic approach. That particular style is most effective when Jian and Guei face off in an abandoned skyscraper, neither willing to give an inch. By keeping us just out of the action, Wang infuses that important neorealist sensibility to the film.

But it’s not enough to make De Sica proud. There’s more repetition than creativity throughout the movie, and in case you’re not sure whether to feel sympathetic for both boys, Wang is sure to remind you. The film’s climax is an interesting shootout of sorts, but plays out as overdramatically as Matt Dillon crawling through the streets at the end of The Outsiders. Beijing Bicycle is a two hour film. After its conclusion, a fellow viewer was asked, “Two hours? Felt more like three, huh?” Repsonse “Felt more like six.”

For more movies like Beijing Bicycle (2001) visit Hurawatch.

Also watch: